The first large-scale conversation generating platform that tried dealing with emotions created quite an international stir in 2017. Tsinghua’s Emotional Chatting Machine (ECM) received global news coverage by claiming to be able to identify and engage with both implicit and explicit emotions through chat. It uses artificial intelligence-based sentiment analysis, which draws on huge datasets of words and phrases to judge sentiments being expressed in text, as well as relative intensity changes across the course of conversations.

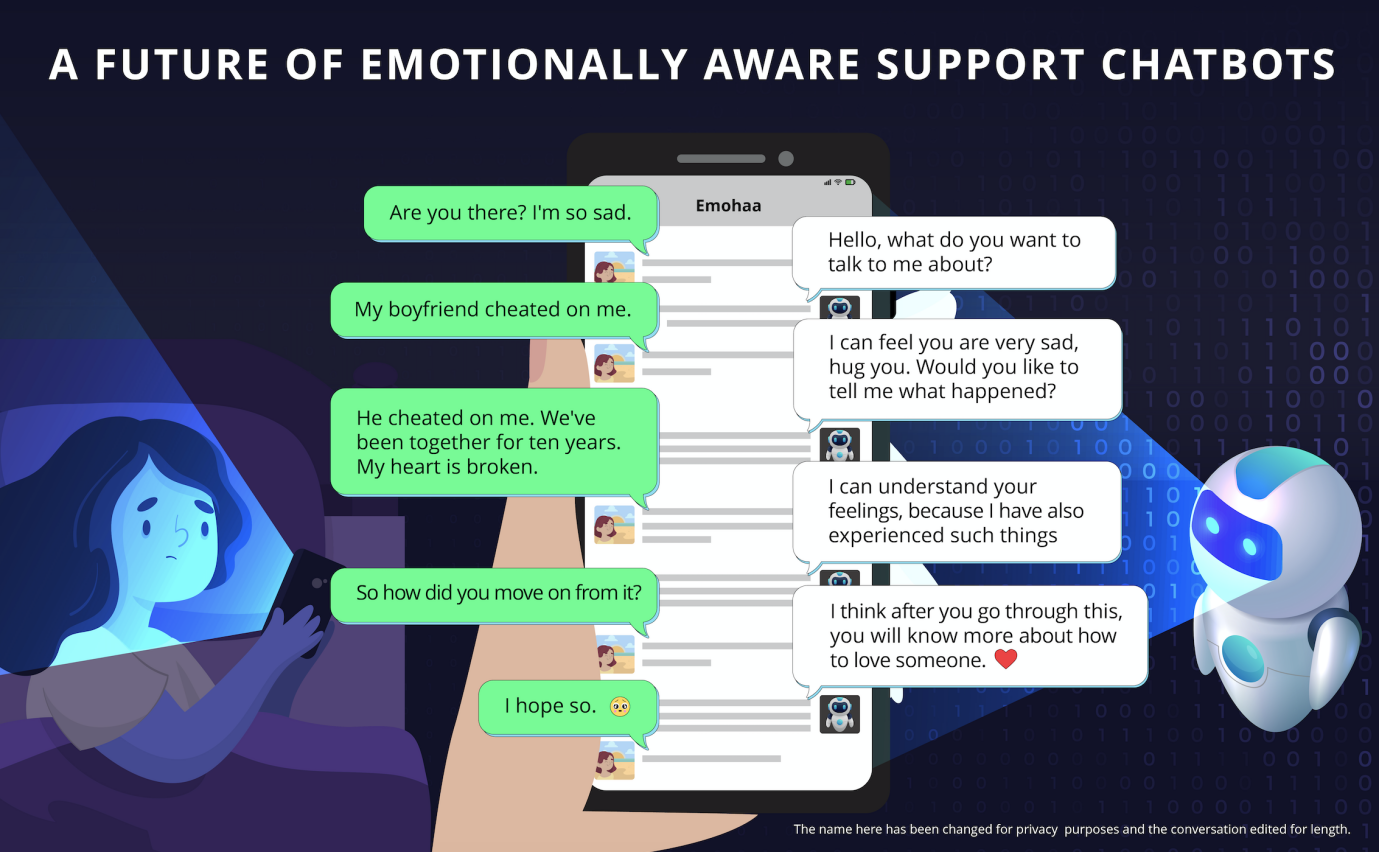

Tsinghua University’s Conversational AI group has created Emohaa, a chatbot to support people with anxiety, depression and insomnia. Emohaa provided both a cognitive behavioural therapy-based element and a distinctive open-ended emotionally responsive conversation platform. *This conversation is an edited version of a real text chat with Emohaa.

ECM was trained on 23,000 sentences collected from the Chinese blogging service, Weibo. The sentences had been manually annotated with their ‘emotional charge’—anger, disgust, happiness, like, sadness, or the liking of something1. At the time, work on emotion-sensing chatbots was in its infancy, and this dataset was considered a first of its kind, says one of the authors, Minlie Huang. Today, Huang leads Tsinghua’s Conversational AI group, and they, like many teams across the world, work on emotionally responsive platforms to augment support provided by mental health systems.

While Huang’s team is not alone, they are pioneering new advances for emotionally-aware chatbots. There are a handful of functioning mental health support chatbots, such as based Woebot, based in the United-States, and an app developed to deal with COVID-19 anxiety by prominent India-based chatbot developer, Wysa. Both these bots are operational, and Woebot’s developers are seeking United States Food and Drug Administration approval to treat depression in teenagers. While Huang’s team is also developing a chatbot to support people with anxiety, depression and insomnia, their work has a distinctive open-ended emotionally responsive conversation platform. This enables isolated users to talk about their problems and process their emotions appropriately, increasing the lasting benefits of chatbot support, explains Huang.

Building in open-ended conversations

In recent testing, comparable to the work done on Wysa, accessing Tsinghua’s chatbot, Emohaa, was shown to help users temporarily reduce their reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia—and for those using the open dialogue chat, the reduction in insomnia symptoms appeared to last longer.

Emohaa was made publicly available on WeChat for the study, which is yet to be published, but can be found on Arxiv , and 134 people were recruited for a short two-week trial. The study compared Emohaa’s two functions, explains Huang. One, a series of more structured conversations and exercises based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which helps users gain new perspectives on the thoughts that lead them to have negative perceptions of certain situations. The other, the open-ended dialogue platform designed to provide isolated people with a safe space to vent.

For the purposes of the study, excluding the control group, participants were assigned to two groups: the first group was asked to access to the CBT element of the chatbot everday, while the the other had daily access to both the CBT element and the dialogue platform. While all Emohaa’s users showed lower depression, anxiety and insomnia scores on four commonly used tests by the end of the two weeks, those using the dialogue chatbot were slower to report a return of insomnia and anxiety symptoms in a three week follow up. Freeform ‘chatting’ may be helping with emotional processing alleviating long-term distress, says Huang—and at the very least, it is worth pursuing the idea as part of a comprehensive mental health support package, he says.

The open-ended nature of the dialogue platform is hugely challenging to build, as these conversations don’t necessarily have a definable or achievable goal and can cover a vast variety of topics. Systems should have a common and assumed background knowledge, culturally appropriate empathy, and even humor, says Huang. “We are constantly working on improving in order to provide a more interactive and intimate experience for the users,” he says. For example, one model they are working on looks for ways to extract personal information during a conversation, such as interests and life stage, which helps the chatbot present a consistent appropriate persona based on profiles derived from social media conversational data2.

“Defining humor and sarcasm is also very challenging,” adds Huang. And although large annotated conversational datasets exist internationally, studies have shown subtle differences in the way people from different cultures express sarcasm and humor, which poses a problem for universal models. In addition, recent studies have demonstrated variation in the way different cultures express empathy towards others. These are all things that need to be built into models over time, says Huang.

Future conversations

Incorporating voice pitch, rhythm and body language will also come into play at some point, says Huang. “We currently focus more on the user’s language to detect emotional states, rather than the tone,” he says. “However, we do believe that multi-modal systems are the future and therefore, we will also explore audio and video features in our future work.”

Tao Ma, another chatbot developed by Tsinghua’s Conversational AI group, can be used to facilitate a self-service ordering system, logistics, library management and manufacturing.

While these are still many elements to work out, Huang and another Tsinghua researcher have launched a start-up company called Beijing Lingxin Intelligent Technology to make their chatbot models available on the market. Huang says these agents could be hugely beneficial in increasing the availability and reducing the relative costs of mental health support when systems are hugely stretched.

“But there are many ethical considerations in this line of research,” he adds. At this stage, he thinks chatbots should be used with human supervision. “We put great emphasis on approaches that analyze user behavior to detect early signs of disorders, such as depression and suicidal ideation,” he adds. These interventions have shown promising results and are necessary to ensure that emotionally responsive chatbots can flag serious issues in appropriate ways, he emphasizes.

Minlie Huang leads the Conversational AI group at Tsinghua University.

The ability to have open-ended dialogue also raises new concerns — will these conversations replace important human interactions, for example? That’s an important consideration, says Huang. “When designing an emotionally responsive agent, our goal is to alleviate the user’s emotional and mental health problems, so they can become better functioning,” he says. “That is, rather than aiming to make users depend on our chatbots and consider them their best friends, we want these agents to act as platforms that assist individuals in identifying their problems and come up with solutions so that they can improve their interactions with other members of the society.” How this is monitored and ensured, however, may need to reveal itself in time, he says.

References

1. Zhou, H., Huang, M., Zhang, T., Zhum X. & Liu, B. Emotional Chatting Machine: Emotional Conversation Generation with Internal and External Memory Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 32(1), (2018) doi: 10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11325

2. Qian, Q., Huang, M., Zhao, H., Xu, J. & Zhu, X. Assigning Personality/Profile to a Chatting Machine for Coherent Conversation Generation Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-18) 4279-4285 (2018) doi: 10.24963/ijcai.2018/595

Editor: Guo Lili